I do not know whether writing ghost stories is a mistake.

Most readers will like a ghost story in which towards the end it is found that the ghost was really a cat or a dog or a mischievous boy.

Such ghost stories are a source of pleasure, and are read as a pastime and are often vastly enjoyed, because though the reader is a bit afraid of what he does not know, still he likes to be assured that ghosts do not in reality exist.

Such ghost stories I have often myself read and enjoyed. The last one I read was in the December (1913) Number of the English Illustrated Magazine. In that story coincidence follows coincidence in such beautiful succession that a young lady really believes that she sees a ghost and even feels its touch, and finally it turns out that it is only a monkey.

This is bathos that unfortunately goes too far. Still, I am sure, English readers love a ghost story of this kind.

It, however, cannot be denied that particular incidents do sometimes happen in such a way that they take our breath away. Here is something [Pg iv] to the point.

"Twenty years ago, near Honey Grove, in Texas, James Ziegland, a wealthy young farmer won the hand of Metilda Tichnor, but jilted her a few days before the day fixed for the marriage. The girl, a celebrated beauty, became despondent and killed herself. Her brother, Phil, went to James Ziegland's home and after denouncing him, fired at him. The bullet grazed the cheek of the faithless lover and buried itself in a tree. Young Tichnor, supposing he had killed the man, put a bullet into his own head, dying instantly. Ziegland, subsequently married a wealthy widow. All this was, of course 20 years ago. The other day the farmer James Ziegland and his son cut down the tree in which Tichnor's bullet had lodged. The tree proved too tough for splitting and so a small charge of dynamite was used. The explosion discharged the long forgotten bullet with great force, it pierced Ziegland's head and he fell mortally wounded. He explained the existence of the mysterious bullet as he lay on his deathbed."—The Pioneer, Allahabad, (India,) 31st January, 1913.

In India ghosts and their stories are looked upon with respect and fear. I have heard all sorts of ghost stories from my nurse and my father's [Pg v] coachman, Abdullah, who used to be my constant companion in my childhood, (dear friend, who is no more), as well as from my friends who are Judges and Magistrates and other responsible servants of Government, and in two cases from Judges of Indian High Courts.

A story told by a nurse or a coachman should certainly not be reproduced in this book. In this book, there are a few of those stories only which are true to the best of the author's knowledge and belief.

Some of these narratives may, no doubt, savour too much of the nature of a Cock and Bull story, but the reader must remember that "there are more things in heaven and earth, etc." and that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction.

The author is responsible for the arrangement of the stories in this volume. Probably they could have been better arranged; but a little thought will make it clear why this particular sequence has been selected.

Calcutta, July 1914.

Since the publication of the first edition my attention has been drawn to a number of very interesting and instructive articles that have been appearing in the papers from time to time. Readers who care for subjects like the present must have themselves noted these; but there is one article which, by reason of the great interest created in the German Kaiser at the present moment, I am forced to reproduce. As permission to reproduce the article was delayed the book was through the press by the time it arrived. I am therefore reproducing here the article as it appeared in "the Occult Review of January 1917". My grateful thanks are due to the proprietors and the Editor of "the Occult Review" but for whose kind permission some of my readers would have been deprived of a most interesting treat.

WILHELM II AND THE WHITE LADY OF THE HOHENZOLLERNS.

By KATHARINE COX. [1]

A great deal has been written and said concerning the various appearances of the famous White Lady of the Hohenzollerns. As long ago as the fifteenth century she was seen, for the [Pg vii] first time, in the old Castle of Neuhaus, in Bohemia, looking out at noon day from an upper window of an uninhabited turret of the castle, and numerous indeed are the stories of her appearances to various persons connected with the Royal House of Prussia, from that first one in the turret window down to the time of the death of the late Empress Augusta, which was, of course, of comparatively recent date. For some time after that event, she seems to have taken a rest; and now, if rumour is to be credited, the apparition which displayed in the past so deep an interest in the fortunes—or perhaps one would be more correct in saying misfortunes—of the Hohenzollern family has been manifesting herself again!

The remarkable occurrences of which I am about to write were related by certain French persons of sound sense and unimpeachable veracity, who happened to be in Berlin a few weeks before the outbreak of the European War. The Kaiser, the most superstitious monarch who ever sat upon the Prussian throne, sternly forbade the circulation of the report of these happenings in his own country, but our gallant Allies across the Channel are, fortunately, not obliged to obey the despotic commands of Wilhelm II, and these persons, therefore, upon their return to France, related, to those interested in such matters, the following story of the great War Lord's three visitations from the dreaded ghost of the Hohenzollerns.

Early in the summer of 1914 it was rumoured, in Berlin, that the White Lady had made her re-appearance. The tale, whispered first of all at Court, spread, gradually amongst the townspeople. The Court, alarmed, tried to suppress it, but it refused to be suppressed, and eventually there was scarcely a man, woman or child in the neighbourhood who did not say—irrespective of whether they believed it or not—that the White Lady, the shadowy spectre whose appearance always foreboded [Pg viii] disaster to the Imperial House, had been recently seen, not once, but three times, and by no less a person than Kaiser Wilhelm himself!

The first of these appearances, so rumour stated, took place one night at the end of June. The hour was late: the Court, which was then in residence at the palace of Potsdam, was wrapped in slumber; all was quiet. There was an almost death-like silence in the palace. In one wing were the apartments of the Empress, where she lay sleeping; in the opposite wing slept one of her sons; the other Princes were in Berlin. In an entirely different part of the royal residence, guarded by three sentinels in a spacious antechamber, sat the Emperor in his private study. He had been lately, greatly engrossed in weighty matters of State, and for some time past it had been his habit to work thus, far into the night. That same evening the Chancellor, von Bethman-Hollweg, had had a private audience of his Majesty, and had left the royal presence precisely at 11-30, carrying an enormous dossier under his arm. The Emperor had accompanied him as far as the door, shaken hands with him, then returned to his work at his writing-desk.

Midnight struck, and still the Emperor, without making the slightest sound, sat on within the room. The guards without began to grow slightly uneasy, for at midnight punctually—not a minute before, not a minute after—it was the Emperor's unfailing custom, when he was working late at night, to ring and order a light repast to be brought to him. Sometimes it used to be a cup of thick chocolate, with hot cakes; sometimes a few sandwiches of smoked ham with a glass of Munich or Pilsen beer—but, as this particular midnight hour struck the guards awaited the royal commands in vain. The Emperor had apparently forgotten to order his midnight meal!

One o'clock in the morning came, and still the Emperor's bell had not sounded. Within the study silence continued to [Pg ix] reign—silence as profound indeed as that of the grave. The uneasiness of the three guards without increased; they glanced at each other with anxious faces. Was their royal master taken ill? All during the day he had seemed to be labouring under the influence of some strange, suppressed excitement, and as he had bidden good-bye to the Chancellor they had noticed that the expression of excitement on his face had increased. That something of grave import was in the air they, and indeed every one surrounding the Emperor, had long been aware, it was just possible that the strain of State affairs was becoming too much for him, and that he had been smitten with sudden indisposition. And yet, after all, he had probably only fallen asleep! Whichever it was, however, they were uncertain how to act. If they thrust ceremony aside and entered the study, they knew that very likely they would only expose themselves to the royal anger. The order was strict, "When the Emperor works in his study no one may enter it without being bidden." Should they inform the Lord Chamberlain of the palace? But, if there was no sufficiently serious reason for such a step, they would incur his anger, almost as terrible to face as that of their royal master.

A little more time dragged by, and at last, deciding to risk the consequences, the guards approached the study. One of them, the most courageous of the three, lifted a heavy curtain, and slowly and cautiously opened the door. He gave one rapid glance into the room beyond, then, returning to his companions said in a low voice and with a terrified gesture towards the interior of the study:

"Look!"

The two guards obeyed him, and an alarming spectacle met their eyes. In the middle of the room, beside a big table littered with papers and military documents, lay the Emperor, stretched full length upon the thick velvet pile carpet, one hand, as if to [Pg x] hide something dreadful from view, across his face. He was quite unconscious, and while two of the guards endeavoured to revive him, the other ran for the doctor. Upon the doctor's arrival they carried him to his sleeping apartments, and after some time succeeded in reviving him. The Emperor then, in trembling accents, told his astounded listeners what had occurred.

Exactly at midnight, according to his custom, he had rung the bell which was the signal that he was ready for his repast. Curiously enough, neither of the guards, although they had been listening for it, had heard that bell.

He had rung quite mechanically, and also mechanically, had turned again to his writing desk directly he had done so. A few minutes later he had heard the door open and footsteps approach him across the soft carpet. Without raising his head from his work he had commenced to say:

"Bring me—"

Then he had raised his head, expecting to see the butler awaiting his orders. Instead his eyes fell upon a shadowy female figure dressed in white, with a long, flowing black veil trailing behind her on the ground. He rose from his chair, terrified, and cried:

"Who are you, and what do you want?"

At the same moment, instinctively, he placed his hand upon a service revolver which lay upon the desk. The white figure, however, did not move, and he advanced towards her. She gazed at him, retreating slowly backwards towards the end of the room, and finally disappeared through the door which gave access to the antechamber without. The door, however, had not opened, and the three guards stationed in the antechamber, as has been already stated, had neither seen nor heard anything of the apparition. At [Pg xi] the moment of her disappearance the Emperor fell into a swoon, remaining in that condition until the guards and the doctor revived him.

Such was the story, gaining ground every day in Berlin, of the first of the three appearances of the White Lady of the Hohenzollerns to the Kaiser. The story of her second appearance to him, which occurred some two or three weeks later, is equally remarkable.

On this occasion she did not visit him at Potsdam, but at Berlin, and instead of the witching hour of midnight, she chose the broad, clear light of day. Indeed, during the whole of her career, the White Lady does not seem to have kept to the time-honoured traditions of most ghosts, and appeared to startled humanity chiefly at night time or in dim uncertain lights. She has never been afraid to face the honest daylight, and that, in my opinion, has always been a great factor in establishing her claim to genuineness. A ghost who is seen by sane people, in full daylight, cannot surely be a mere legendary myth!

It was an afternoon of bright summer—that fateful summer whose blue skies were so soon to be darkened by the sinister clouds of war! The Royal Standard, intimating to the worthy citizens of Berlin the presence of their Emperor, floated gaily over the Imperial residence in the gentle breeze. The Emperor, wrapped in heavy thought—there was much for the mighty War Lord to think about during those last pregnant days before plunging Europe into an agony of tears and blood!—was pacing, alone, up and down a long gallery within the palace.

His walk was agitated; there was a troubled frown upon his austere countenance. Every now and then he paused in his walk, and withdrew from his pocket a piece of paper, which he carefully read and re-read, and as he did so, angry, muttered [Pg xii] words broke from him, and his hand flew instinctively to his sword hilt. Occasionally he raised his eyes to the walls on either side of him, upon which hung numerous portraits of his distinguished ancestors. He studied them gravely, from Frederick I, Burgrave of Nuremburg, to that other Frederick, his own father, and husband of the fair English princess against whose country he was so shortly going to wage the most horrible warfare that has ever been waged in the whole history of the world!

Suddenly, from the other end of the long portrait gallery he perceived coming towards him a shadowy female figure, dressed entirely in white, and carrying a large bunch of keys in her hand. She was not, this time, wearing the long flowing black veil in which she had appeared to him a few weeks previously, but the Emperor instantly recognized her, and the blood froze in his veins. He stood rooted to the ground, unable to advance or to retreat, paralysed with horror, the hair rising on his head, beads of perspiration standing on his brow.

The figure continued to advance in his direction, slowly, noiselessly, appearing rather to glide than to walk over the floor. There was an expression of the deepest sadness upon her countenance, and as she drew near to the stricken man watching her, she held out her arms towards him, as if to enfold him. The Emperor, his horror increasing, made a violent effort to move, but in vain. He seemed indeed paralysed; his limbs, his muscles, refused to obey him.

Then suddenly, just as the apparition came close up to him and he felt, as on the former occasion when he had been visited by her, that he was going to faint, she turned abruptly and moved away in the direction of a small side door. This she opened with her uncanny bunch of keys and without turning her head, disappeared.

[Pg xiii] At the exact moment of her disappearance the Emperor recovered his faculties. He was able to move, he was able to speak; his arms, legs, tongue, obeyed his autocratic will once more. He uttered a loud terrified cry, which resounded throughout the palace. Officers, chamberlains, guards, servants, came running to the gallery, white-faced, to see what had happened. They found their royal master in a state bordering on collapse. Yet, to the anxious questions which they put to him, he only replied incoherently and evasively; it was as if he knew something terrible, something dreadful, but did not wish to speak of it. Eventually he retired to his own apartments, but it was not until several hours had passed that he returned to his normal condition of mind.

The same doctor who had been summoned on the occasion of Wilhelm's former encounter with the White Lady was in attendance on him, and he looked extremely grave when informed that the Emperor had again experienced a mysterious shock. He shut himself up alone with his royal patient, forbidding any one else access to the private apartments. However, in spite of all precautions, the story of what had really occurred in the picture gallery eventually leaked out—it is said through a maid of honour, who heard it from the Empress.

The third appearance of the White Lady of the Hohenzollerns to the Kaiser did not take place at either of the palaces, but strangely enough, in a forest, though exactly where situated has not been satisfactorily verified.

In the middle of the month of July, 1914, while the war-clouds were darkening every hour, the Emperor's movements were very unsettled. He was constantly travelling from place to place, and one day—so it was afterwards said in Berlin—while on a hunting expedition, he suddenly encountered a phantom female figure, dressed in white, who, springing apparently [Pg xiv] from nowhere, stopped in front of his horse, and blew a shadowy horn, frightening the animal so much that its rider was nearly thrown to the ground. The phantom figure then disappeared, as mysteriously as it had come—but that it was the White Lady of the Hohenzollerns, come, perchance, to warn Wilhelm of some terrible future fate, there was little doubt in the minds of those who afterwards heard of the occurrence.

According to one version of the story of this third appearance, the phantom was also seen by two officers who were riding by the Emperor's side, but the general belief is that she manifested herself, as on the two former occasions, to Wilhelm alone.

There are many who will not believe in the story, no doubt, and there are also many who will. For my own part, I am inclined to think that, if the ghost of the Hohenzollerns was able to manifest herself so often on the eve of any tragedy befalling them in past, it would be strange indeed if she had not manifested herself on the eve of this greatest tragedy of all—the War!

Allahabad ,

July 18th, 1917.

[1] The writer desires to acknowledge her indebtedness for much of the information contained in this article to J.H. Lavaur's "La Dame Blanche des Hohenzollern et Guillaume II" (Paris: 56 Rue d'Aboukir).

This story created a sensation when it was first told. It appeared in the papers and many big Physicists and Natural Philosophers were, at least so they thought, able to explain the phenomenon. I shall narrate the event and also tell the reader what explanation was given, and let him draw his own conclusions.

This was what happened.

A friend of mine, a clerk in the same office as myself, was an amateur photographer; let us call him Jones.

Jones had a half plate Sanderson camera with a Ross lens and a Thornton Picard behind lens shutter, with pneumatic release. The plate in question was a Wrattens ordinary, developed with Ilford Pyro Soda developer prepared at home. All these particulars I give for the benefit of the more technical reader.

[Pg 2] Mr. Smith, another clerk in our office, invited Mr. Jones to take a likeness of his wife and sister-in-law.

This sister-in-law was the wife of Mr. Smith's elder brother, who was also a Government servant, then on leave. The idea of the photograph was of the sister-in-law.

Jones was a keen photographer himself. He had photographed every body in the office including the peons and sweepers, and had even supplied every sitter of his with copies of his handiwork. So he most willingly consented, and anxiously waited for the Sunday on which the photograph was to be taken.

Early on Sunday morning, Jones went to the Smiths'. The arrangement of light in the verandah was such that a photograph could only be taken after midday; and so he stayed there to breakfast.

At about one in the afternoon all arrangements were complete and the two ladies, Mrs. Smiths, were made to sit in two cane chairs and after long and careful focussing, and moving the camera about for an hour, Jones was satisfied at last and an exposure was made. Mr. Jones was sure that [Pg 3] the plate was all right; and so, a second plate was not exposed although in the usual course of things this should have been done.

He wrapped up his things and went home promising to develop the plate the same night and bring a copy of the photograph the next day to the office.

The next day, which was a Monday, Jones came to the office very early, and I was the first person to meet him.

"Well, Mr. Photographer," I asked "what success?"

"I got the picture all right," said Jones, unwrapping an unmounted picture and handing it over to me "most funny, don't you think so?" "No, I don't . I think it is all right, at any rate I did not expect anything better from you . ", I said.

"No," said Jones "the funny thing is that only two ladies sat . " "Quite right," I said "the third stood in the middle."

"There was no third lady at all there . ", said Jones.

"Then you imagined she was there, and there we find her . " "I tell you, there were only two [Pg 4] ladies there when I exposed" insisted Jones. He was looking awfully worried.

"Do you want me to believe that there were only two persons when the plate was exposed and three when it was developed?" I asked. "That is exactly what has happened," said Jones.

"Then it must be the most wonderful developer you used, or was it that this was the second exposure given to the same plate?"

"The developer is the one which I have been using for the last three years, and the plate, the one I charged on Saturday night out of a new box that I had purchased only on Saturday afternoon."

A number of other clerks had come up in the meantime, and were taking great interest in the picture and in Jones' statement.

It is only right that a description of the picture be given here for the benefit of the reader. I wish I could reproduce the original picture too, but that for certain reasons is impossible.

When the plate was actually exposed there were only two ladies, both of whom were sitting in cane chairs. When the plate was developed it was found that there was in the picture a figure, [Pg 5] that of a lady, standing in the middle. She wore a broad-edged dhoti (the reader should not forget that all the characters are Indians), only the upper half of her body being visible, the lower being covered up by the low backs of the cane chairs. She was distinctly behind the chairs, and consequently slightly out of focus. Still everything was quite clear. Even her long necklace was visible through the little opening in the dhoti near the right shoulder. She was resting her hands on the backs of the chairs and the fingers were nearly totally out of focus, but a ring on the right ring-finger was clearly visible. She looked like a handsome young woman of twenty-two, short and thin. One of the ear-rings was also clearly visible, although the face itself was slightly out of focus. One thing, and probably the funniest thing, that we overlooked then but observed afterwards, was that immediately behind the three ladies was a barred window. The two ladies, who were one on each side, covered up the bars to a certain height from the bottom with their bodies, but the lady in the middle was partly transparent because the bars of the window were very faintly visible through her. This fact, however, as I have said already, we did not observe then. We only laughed at Jones and [Pg 6] tried to assure him that he was either drunk or asleep. At this moment Smith of our office walked in, removing the trouser clips from his legs.

Smith took the unmounted photograph, looked at it for a minute, turned red and blue and green and finally very pale. Of course, we asked him what the matter was and this was what he said:

"The third lady in the middle was my first wife, who has been dead these eight years. Before her death she asked me a number of times to have her photograph taken. She used to say that she had a presentiment that she might die early. I did not believe in her presentiment myself, but I did not object to the photograph. So one day I ordered the carriage and asked her to dress up. We intended to go to a good professional. She dressed up and the carriage was ready, but as we were going to start news reached us that her mother was dangerously ill. So we went to see her mother instead. The mother was very ill, and I had to leave her there. Immediately afterwards I was sent away on duty to another station and so could not bring her back. It was in fact after full three months and a half that I returned and then though her mother was all right, my [Pg 7] wife was not. Within fifteen days of my return she died of puerperal fever after child-birth and the child died too. A photograph of her was never taken. When she dressed up for the last time on the day that she left my home she had the necklace and the ear-rings on, as you see her wearing in the photograph. My present wife has them now but she does not generally put them on."

This was too big a pill for me to swallow. So I at once took French leave from my office, bagged the photograph and rushed out on my bicycle. I went to Mr. Smith's house and looked Mrs. Smith up. Of course, she was much astonished to see a third lady in the picture but could not guess who she was. This I had expected, as supposing Smith's story to be true, this lady had never seen her husband's first wife. The elder brother's wife, however, recognized the likeness at once and she virtually repeated the story which Smith had told me earlier that day. She even brought out the necklace and the ear-rings for my inspection and conviction. They were the same as those in the photograph.

All the principal newspapers of that time got hold of the fact and within a week there was any [Pg 8] number of applications for the ghostly photograph. But Mr. Jones refused to supply copies of it to anybody for various reasons, the principal being that Smith would not allow it. I am, however, the fortunate possessor of a copy which, for obvious reasons, I am not allowed to show to anybody. One copy of the picture was sent to America and another to England. I do not now remember exactly to whom. My own copy I showed to the Rev. Father —— m.a., d.sc., b.d. , etc., and asked him to find out a scientific explanation of the phenomenon. The following explanation was given by the gentleman. (I am afraid I shall not be able to reproduce the learned Father's exact words, but this is what he meant or at least what I understood him to mean).

"The girl in question was dressed in this particular way on an occasion, say 10 years ago. Her image was cast on space and the reflection was projected from one luminous body (one planet) on another till it made a circuit of millions and millions of miles in space and then came back to earth at the exact moment when our friend, Mr. Jones, was going to make the exposure.

"Take for instance the case of a man who is taking the photograph of a mirage. He is photo [Pg 9] graphing place X from place Y, when X and Y are, say, 200 miles apart, and it may be that his camera is facing east while place X is actually towards the west of place Y."

In school I had read a little of Science and Chemistry and could make a dry analysis of a salt; but this was an item too big for my limited comprehension.

The fact, however, remains and I believe it, that Smith's first wife did come back to this terrestrial globe of ours over eight years after her death to give a sitting for a photograph in a form which, though it did not affect the retina of our eye, did impress a sensitized plate; in a form that did not affect the retina of the eye, I say, because Jones must have been looking at his sitters at the time when he was pressing the bulb of the pneumatic release of his time and instantaneous shutter.

The story is most wonderful but this is exactly what happened. Smith says this is the first time he has ever seen, or heard from, his dead wife. It is popularly believed in India that a dead wife gives a lot of trouble, if she ever revisits this earth, but this is, thank God, not the experience of my friend, Mr. Smith.

[Pg 10] It is now over seven years since the event mentioned above happened; and the dead girl has never appeared again. I would very much like to have a photograph of the two ladies taken once more; but I have never ventured to approach Smith with the proposal. In fact, I learnt photography myself with a view to take the photograph of the two ladies, but as I have said, I have never been able to speak to Smith about my intention, and probably never shall. The £10, that I spent on my cheap photographic outfit may be a waste. But I have learnt an art which though rather costly for my limited means is nevertheless an art worth learning.

A curious little story was told the other day in a certain Civil Court in British India.

A certain military officer, let us call him Major Brown, rented a house in one of the big Cantonment stations where he had been recently transferred with his regiment.

This gentleman had just arrived from England with his wife. He was the son of a rich man at home and so he could afford to have a large house. This was the first time he had come out to India and was consequently rather unacquainted with the manners and customs of this country.

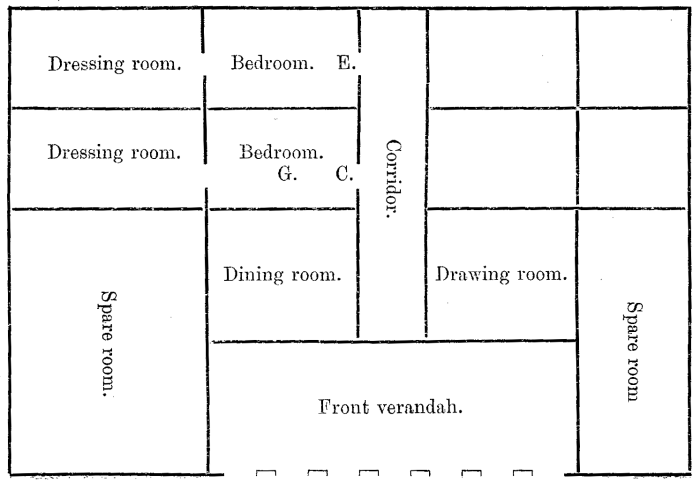

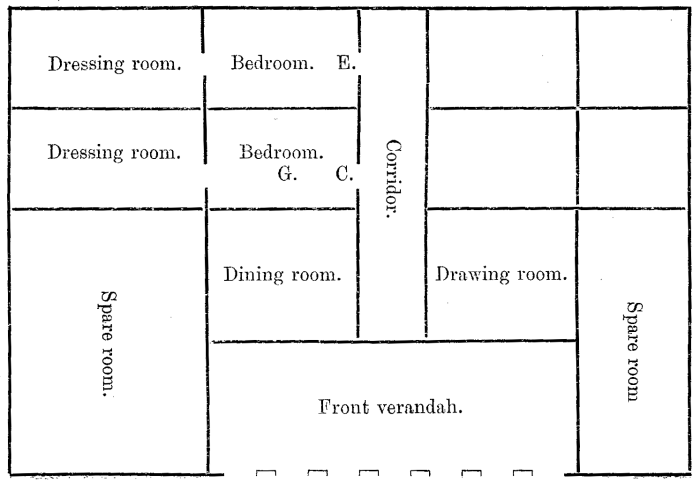

This is a rough plan, the original of which was probably in the Major's handwriting.

Major Brown took this house on a long lease and thought he had made a bargain. The house was large and stood in the centre of a very spacious compound. There was a garden which appeared to have been carefully laid out once, but as the house had no tenant for a long time the garden looked more like a wilderness. There were two very well kept lawn tennis courts and these were a great attraction to the Major, who was very keen on tennis. The stablings and out-houses were commodious and the Major, who was thinking of keeping a few polo ponies, found the whole thing very satisfactory. Over and above everything he found the landlord very obliging. He had heard on board the steamer on his way out that Indian landlords were the worst class of human beings one could come across on the face of this earth (and that is very true), but this particular landlord looked like an exception to the general rule.

He consented to make at his own expense all the alterations that the Major wanted him to do, and these alterations were carried out to Major and Mrs. Brown's entire satisfaction.

On his arrival in this station Major Brown had put up at an hotel and after some alterations had been made he ordered the house to be furnished. This was done in three or four days and then he moved in.

Annexed is a rough sketch of the house in question. The house was a very large one and there was a number of rooms, but we have nothing to do with all of them. The spots marked "C" and "E" represent the doors.

Now what happened in Court was this:

[Pg 14] After he had occupied the house for not over three weeks the Major and his wife cleared out and took shelter again in the hotel from which they had come. The landlord demanded rent for the entire period stipulated for in the lease and the Major refused to pay. The matter went to Court. The presiding Judge, who was an Indian gentleman, was one of the cleverest men in the service, and he thought it was a very simple case.

When the case was called on the plaintiff's pleader said that he would begin by proving the lease. Major Brown, the defendant, who appeared in person, said that he would admit it. The Judge who was a very kind hearted gentleman asked the defendant why he had vacated the house.

"I could not stay," said the Major "I had every intention of living in the house, I got it furnished and spent two thousand rupees over it, I was laying out a garden. "

"But what do you mean by saying that you could not stay?"

"If your Honour passed a night in that house, you would understand what I meant," said the Major.

[Pg 15] "You take the oath and make a statement," said the Judge. Major Brown then made the following statement on oath in open Court.

"When I came to the station I saw the house and my wife liked it. We asked the landlord whether he would make a few alterations and he consented. After the alterations had been carried out I executed the lease and ordered the house to be furnished. A week after the execution of the lease we moved in. The house is very large."

Here followed a description of the building; but to make matters clear and short I have copied out the rough pencil sketch which is still on the record of the case and marked the doors and rooms, as the Major had done, with letters.

"I do not dine at the mess. I have an early dinner at home with my wife and retire early. My wife and I sleep in the same bedroom (the room marked "G" in the plan), and we are generally in bed at about 11 o'clock at night. The servants all go away to the out-houses which are at a distance of about 40 yards from the main building, only one Jamadar (porter) remains in the front verandah. This Jamadar also keeps an eye on the whole main building, besides I have got [Pg 16] a good, faithful watch dog which I brought out from home. He stays outside with the Jamadar.

"For the first fifteen days we were quite comfortable, then the trouble began.

"One night before dinner my wife was reading a story, a detective story, of a particularly interesting nature. There were only a few more pages left and so we thought that she would finish them before we put out the reading lamp. We were in the bedroom. But it took her much longer than she had expected it would, and so it was actually half an hour after midnight when we put out the big sixteen candle power reading lamp which stood on a teapoy near the head of the beds. Only a small bedroom lamp remained.

"But though we put out the light we did not fall asleep. We were discussing the cleverness of the detective and the folly of the thief who had left a clue behind, and it was actually two o'clock when we pulled our rugs up to our necks and closed our eyes.

"At that moment we heard the footsteps of a number of persons walking along the corridor. The corridor runs the whole length of the house as will appear from the rough sketch. This corri [Pg 17] dor was well carpeted still we heard the tread of a number of feet. We looked at the door "C." This door was closed but not bolted from inside. Slowly it was pushed open, and, horror of horrors, three shadowy forms walked into the room. One was distinctly the form of a white man in European night attire, another the form of a white woman, also in night attire, and the third was the form of a black woman, probably an Indian nurse or ayah.

"We remained dumb with horror, as we could see clearly that these unwelcome visitors were not of this world. We could not move.

"The three figures passed right round the beds as if searching for something. They looked into every nook and corner of the bed-room and then passed into the dressing room. Within half a minute they returned and passed out into the corridor in the same order in which they had come in, namely, the man first, the white woman next, and the black woman last of all.

"We lay as if dead. We could hear them in the corridor and in the bedroom adjoining, with the door "E", and in the dressing room attached to that bedroom. They again returned and passed into the corridor . and then we could hear them no more.

[Pg 18] "It must have taken me at least five minutes to collect my senses and to bring my limbs under control. When I got up I found that my wife had fainted. I hurried out of the room, rushed along the corridor, opened the front door and called the servants. The servants were all approaching the house across the land which separated the servants' quarters from the main building. Then I went into the dining room, and procuring some brandy, gave it to my wife. It was with some difficulty that I could make her swallow it, but it revived her and she looked at me with a bewildered smile on her face.

"The servants had in the meantime arrived and were in the corridor. Their presence had the effect of giving us some courage. Leaving my wife in bed I went out and related to the servants what I had seen. The Chaukidar (the night watchman) who was an old resident of the compound (in fact he had been in charge of the house when it was vacant, before I rented it) gave me the history of the ghost, which my Jamadar interpreted to me. I have brought the Chaukidar and shall produce him as my witness."

This was the statement of the Major. Then there was the statement of Jokhi Passi, Chaukidar, defendant's witness.

[Pg 19] The statement of this witness as recorded was as follows:

"My age is 60 years. At the time of the Indian Mutiny I was a full-grown young man. This house was built at that time. I mean two or three years after the Mutiny. I have always been in charge. After the Mutiny one Judge came to live in the house. He was called Judge Parson (probably Pearson). The Judge had to try a young Muhammadan charged with murder and he sentenced the youth to death. The aged parents of the young man vowed vengeance against the good Judge. On the night following the morning on which the execution took place it appeared that certain undesirable characters were prowling about the compound. I was then the watchman in charge as I am now. I woke up the Indian nurse who slept with the Judge's baby in a bed-room adjoining the one in which the Judge himself slept. On waking up she found that the baby was not in its cot. She rushed out of the bed-room and informed the Judge and his wife. Then a feverish search began for the baby, but it was never found. The police were communicated with and they arrived at about four in the morning. The police enquiry lasted for about half an hour [Pg 20] and then the officers went away promising to come again. At last the Judge, his wife, and nurse all retired to their respective beds where they were found lying dead later in the morning. Another police enquiry took place, and it was found that death was due to snake-bite. There were two small punctures on one of the legs of each victim. How a snake got in and killed each victim in turn, especially when two slept in one room and the third in another, and finally got out, has remained a mystery. But the Judge, his wife, and the nurse are still seen on every Friday night looking for the missing baby. One rainy season the servants' quarters were being re-roofed. I had then an occasion to sleep in the corridor; and thus I saw the ghosts. At that time I was as afraid as the Major Saheb is to-day, but then I soon found out that the ghosts were quite harmless."

This was the story as recorded in Court. The Judge was a very sensible man (I had the pleasure and honour of being introduced to him about 20 years after this incident), and with a number of people, he decided to pass one Friday night in the haunted house. He did so. What he saw does not appear from the record; for he left no inspection [Pg 21] notes and probably he never made any. He delivered judgment on Monday following. It is a very short judgment.

After reciting the facts the judgment proceeds: "I have recorded the statements of the defendant and a witness produced by him. I have also made a local inspection. I find that the landlord, (the plaintiff) knew that for certain reasons the house was practically uninhabitable, and he concealed that fact from his tenant. He, therefore, could not recover. The suit is dismissed with costs."

The haunted house remained untenanted for a long time. The proprietor subsequently made a gift of it to a charitable institution. The founders of this institution, who were Hindus and firm believers in charms and exorcisms, had some religious ceremony performed on the premises. Afterwards the house was pulled down and on its site now stands one of the grandest buildings in the station, that cost fully ten thousand pounds. Only this morning I received a visit from a gentleman who lives in the building, referred to above, but evidently he has not even heard of the ghosts of the Judge, his wife, and his Indian ayah.

It is now nearly fifty years; but the missing baby has not been heard of. If it is alive it has [Pg 22] grown into a fully developed man. But does he know the fate of his parents and his nurse?

In this connection it will not be out of place to mention a fact that appeared in the papers some years ago.

A certain European gentleman was posted to a district in the Madras Presidency as a Government servant in the Financial Department.

When this gentleman reached the station to which he had been posted he put up at the Club, as they usually do, and began to look out for a house, when he was informed that there was a haunted house in the neighbourhood. Being rather sceptical he decided to take this house, ghost or no ghost. He was given to understand by the members of the Club that this house was a bit out of the way and was infested at night with thieves and robbers who came to divide their booty in that house; and to guard against its being occupied by a tenant it had been given a bad reputation. The proprietor being a wealthy old native of the old school did not care to investigate. So our friend, whom we shall, for the purposes of this story, call Mr. Hunter, took the house at a fair rent.

The house was in charge of a Chaukidar (care-taker, porter or watchman) when it was [Pg 23] vacant. Mr. Hunter engaged the same man as a night watchman for this house. This Chaukidar informed Mr. Hunter that the ghost appeared only one day in the year, namely, the 21st of September, and added that if Mr. Hunter kept out of the house on that night there would be no trouble.

"I always keep away on the night of the 21st September," said the watchman.

"And what kind of ghost is it?" asked Mr. Hunter.

"It is a European lady dressed in white," said the man. "What does she do?" asked Mr. Hunter.

"Oh! she comes out of the room and calls you and asks you to follow her," said the man.

"Has anybody ever followed her?"

"Nobody that I know of, Sir," said the man. "The man who was here before me saw her and died from fear."

"Most wonderful! But why do not people follow her in a body?" asked Mr. Hunter.

"It is very easy to say that, Sir, but when you see her you will not like to follow her yourself. I have been in this house for over 20 years, lots of times European soldiers have passed the night [Pg 24] of the 21st September, intending to follow her but when she actually comes nobody has ever ventured."

"Most wonderful! I shall follow her this time," said Mr. Hunter.

"As you please Sir," said the man and retired.

It was one of the duties of Mr. Hunter to distribute the pensions of all retired Government servants.

In this connection Mr. Hunter used to come in contact with a number of very old men in the station who attended his office to receive their pensions from him.

By questioning them Mr. Hunter got so far that the house had at one time been occupied by a European officer.

This officer had a young wife who fell in love with a certain Captain Leslie. One night when the husband was out on tour (and not expected to return within a week) his wife was entertaining Captain Leslie. The gentleman returned unexpectedly and found his wife in the arms of the Captain.

[Pg 25] He lost his self-control and attacked the couple with a meat chopper—the first weapon that came handy.

Captain Leslie moved away and then cleared out leaving the unfortunate wife at the mercy of the infuriated husband. He aimed a blow at her head which she warded off with her hand. But so severe was the blow that the hand was cut off and the woman fell down on the ground quite unconscious. The sight of blood made the husband mad. Subsequently the servants came up and called a doctor, but by the time the doctor arrived the woman was dead.

The unfortunate husband who had become raving mad was sent to a lunatic asylum and thence taken away to England. The body of the woman was in the local cemetery; but what had become of the severed hand was not known. The missing limb had never been found. All this was 50 years ago, that is, immediately after the Indian Mutiny.

This was what Mr. Hunter gathered.

The 21st September was not very far off. Mr. Hunter decided to meet the ghost.

[Pg 26] The night in question arrived, and Mr. Hunter sat in his bed-room with his magazine. The lamp was burning brightly.

The servants had all retired, and Mr. Hunter knew that if he called for help nobody would hear him, and even if anybody did hear, he too would not come.

He was, however, a very bold man and sat there awaiting developments.

At one in the morning he heard footsteps approaching the bed-room from the direction of the dining-room.

He could distinctly hear the rustle of the skirts. Gradually the door between the two rooms began to open wide. Then the curtain began to move. Mr. Hunter sat with straining eyes and beating heart.

At last she came in. The Englishwoman in flowing white robes. Mr. Hunter sat panting unable to move. She looked at him for about a minute and beckoned him to follow her. It was then that Mr. Hunter observed that she had only one hand.

He got up and followed her. She went back to the dining-room and he followed her there. [Pg 27] There was no light in the dining-room but he could see her faintly in the dark. She went right across the dining-room to the door on the other side which opened on the verandah. Mr. Hunter could not see what she was doing at the door, but he knew she was opening it.

When the door opened she passed out and Mr. Hunter followed. Then she walked across the verandah down the steps and stood upon the lawn. Mr. Hunter was on the lawn in a moment. His fears had now completely vanished. She next proceeded along the lawn in the direction of a hedge. Mr. Hunter also reached the hedge and found that under the hedge were concealed two spades. The gardener must have been working with them and left them there after the day's work.

The lady made a sign to him and he took up one of the spades. Then again she proceeded and he followed.

They had reached some distance in the garden when the lady with her foot indicated a spot and Mr. Hunter inferred that she wanted him to dig there. Of course, Mr. Hunter knew that he was not going to discover a treasure-trove, but he was sure he was going to find something very interest [Pg 28] ing. So he began digging with all his vigour. Only about 18 inches below the surface the blade struck against some hard substance. Mr. Hunter looked up.

The apparition had vanished. Mr. Hunter dug on and discovered that the hard substance was a human hand with the fingers and everything intact. Of course, the flesh had gone, only the bones remained. Mr. Hunter picked up the bones and knew exactly what to do.

He returned to the house, dressed himself up in his cycling costume and rode away with the bones and the spade to the cemetery. He waked the night watchman, got the gate opened, found out the tomb of the murdered woman and close to it interred the bones, that he had found in such a mysterious fashion, reciting as much of the service as he could remember. Then he paid some buksheesh (reward) to the night watchman and came home.

He put back the spade in its old place and retired. A few days after he paid a visit to the cemetery in the day-time and found that grass had grown on the spot which he had dug up. The bones had evidently not been disturbed.

[Pg 29] The next year on the 21st September Mr. Hunter kept up the whole night, but he had no visit from the ghostly lady.

The house is now in the occupation of another European gentleman who took it after Mr. Hunter's transfer from the station and this new tenant had no visit from the ghost either. Let us hope that "she" now rests in peace.

The following extract from a Bengal newspaper that appeared in September 1913, is very interesting and instructive.

"The following extraordinary phenomenon took place at the Hooghly Police Club Building, Chinsurah, at about midnight on last Saturday.

"At this late hour of the night some peculiar sounds of agony on the roof of the house aroused the resident members of the Club, who at once proceeded to the roof with lamps and found to their entire surprise a lady clad in white jumping from the roof to the ground (about a hundred feet in height) followed by a man with a dagger in his hands. But eventually no trace of it could be [Pg 30] found on the ground. This is not the first occasion that such beings are found to visit this house and it is heard from a reliable source that long ago a woman committed suicide by hanging and it is believed that her spirit loiters round the building. As these incidents have made a deep impression upon the members, they have decided to remove the Club from the said buildings."

Here again is something that is very peculiar and not very uncommon.

We, myself and three other friends of mine, were asked by another friend of ours to pass a week's holiday at the suburban residence of the last named. We took an evening train after the office hours and reached our destination at about 10-30 at night. The place was about 60 miles from Calcutta.

Our host had a very large house with a number of disused wings. I do not think many of my readers have any idea of a large residential house in Bengal. Generally it is a quadrangular sort of thing with a big yard in the centre which is called the "Angan" or "uthan" (a court-yard). On all sides of the court-yard are rooms of all sorts of shapes and sizes. There are generally two stories—the lower used as kitchen, godown, store-room, etc., and the upper as bed-rooms, etc.

Now this particular house of our friend was of the kind described above. It stood on extensive grounds wooded with fruit and timber trees. There was also a big tank, a miniature lake in fact, which was the property of my friend. There was good fishing in the lake and that was the particular attraction that had drawn my other friends to this place. I myself was not very fond of angling.

As I have said we reached this place at about 10-30 at night. We were received very kindly by the father and the mother of our host who were a very jolly old couple; and after a very late supper, or, shall I call it dinner, we retired. The guest rooms were well furnished and very comfortable. It was a bright moonlight night and our plan was to get up at 4 in the morning and go to the lake for angling.

At three in the morning the servants of our host woke us up (they had come to carry our fishing gear) and we went to the lake which was a couple of hundred yards from the house. As I have said it was a bright moonlight night in summer and the outing was not unpleasant after all. We remained on the bank of the lake till about seven in the morning, when one of the servants came to fetch us for our morning tea. I may as well mention here that breakfast in India generally means a pretty heavy meal at about 10 a.m.

[Pg 34] I was the first to get up; for I have said already that I was not a worthy disciple of Izaak Walton. I wound up my line and walked away, carrying my rod myself.

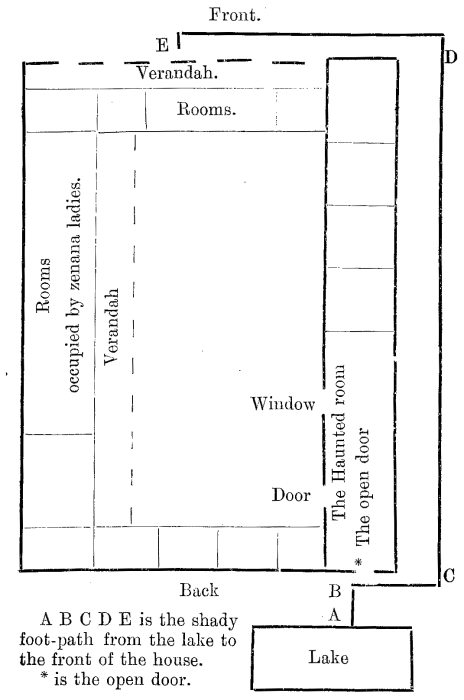

The lake was towards the back of the house. To come from the lake to the front of it we had to pass along the whole length of the buildings. See rough plan above.

As would appear from the plan we had to pass along the shady foot-path ABCDE, there was a turning at each point B, C, D and E. The back row of rooms was used for godowns, store-rooms, kitchens, etc. One room, the one with a door marked "*" at the corner, was used for storing a number of door-frames. The owner of the house, our host's father, had at one time contemplated adding a new wing and for that purpose the door-frames had been made. Then he gave up the idea and the door-frames were kept stored up in that corner-room with a door on the outside marked "*". Now as I was walking ahead I reached the turning B first of all and it was probably an accident that the point of my rod touched the door. The door flew open. I knew this was an unused portion of the house and so the opening of the door surprised me to a certain [Pg 35] extent. I looked into the room and discovered the wooden door-frames. There was nothing peculiar about the room or its contents either.

When we were drinking our tea five minutes later I casually remarked that they would find some of the door-frames missing as the door of the room in which they were kept had been left open all night. I did not at that time attach any importance to a peculiar look of the eyes of the old couple, my host's father and mother. The old gentleman called one of the servants and ordered him to bolt that door.

When we were going to the lake in the evening I examined the door and found that it had been closed from inside.

The next morning we went out a-fishing again and we were returning for our tea, at about 7 in the morning. I was again ahead of all the rest. As I came along, this time intentionally I gave a push to the door with my rod. It again flew open. "This is funny" I thought.

At tea I reported the matter to the old couple and I then noticed with curiosity their embarrassed look of the day before. I therefore suggested that the servants intentionally left the door open, [Pg 36] and one morning they would find the door-frames, stored in the room, gone.

At this the old man smiled. He said that the door of this particular room had remained open for the last 15 years and the contents had never been disturbed. On our pressing him why the door remained open he admitted with great reluctance that since the death of a certain servant of the house-hold in that particular room fifteen years ago the outer door had never remained closed. "You may close it yourself and see" suggested the old gentleman.

We required no further invitation. Immediately we all went to that room to investigate and find out the ghost if he remained indoors during the day. But Mr. Ghost was not there. "He has gone out for his morning constitutional," I suggested, "and this time we shall keep him out." Now this particular room had two doors and one window. The window and one door were on the court-yard side of the room and communicated with the court-yard. The other door led to the grounds outside and this last was the haunted door. We opened both the doors and the window and examined the room. There was nothing extraordinary about it. Then we tried to close the [Pg 37] haunted door. It had warped probably by being kept open for 15 years. It had two very strong bolts on the inside but the lower bolt would not go within 3 inches of its socket. The upper one was very loose and a little continuous thumping would bring the bolt down. We thought we had solved the mystery thus:—The servants only closed the door by pushing up the upper bolt, at night the wind would shake the door and the bolt would come down. So this time we took good care to use the lower bolt. Three of us pushed the door with all our might and one man thrust the lower bolt into its socket. It hardly went in a quarter of an inch, but still the door was secure. We then hammered the bolt in with bricks. In doing this we broke about half a dozen of them. This will explain to the reader how much strength it required to drive the bolt in about an inch and a half.

Then we satisfied ourselves that the bolt could not be moved without the aid of a hammer and a lever. Afterwards we closed the window and the other door and securely locked the last. Thus no human being could open the haunted door.

Before retiring to bed after dinner we further examined both the doors once more. They were all right.

[Pg 38] The next morning we did not go out for fishing; so when we got up at about five in the morning the first thing we did was to go and examine the haunted door. It flew in at the touch. We then went inside and examined the other door and the window which communicated with the court-yard. The window was as secure as we had left it and the door was chained from outside. We went round into the court-yard and examined the lock. It did not appear to have been tampered with.

The old man and his wife met us at tea as usual. They had evidently been told everything. They, however, did not mention the subject, neither did we.

It was my intention to pass a night in that room but nobody would agree to bear me company, and I did not quite like the idea of passing a whole night in that ugly room. Moreover my hosts would not have heard of it.

The mystery of the open door has not yet been solved. It was about 20 years ago that what I have narrated above, happened. I am not sure that the mystery will ever be solved.

In this connection it will not be out of place to mention another incident with regard to another family and another house in another part of Bengal.

[Pg 39] Once while coming back from Darjeeling, the summer capital of Bengal, I had a very garrulous old gentleman for a fellow traveller in the same compartment. I was reading a copy of the Occult Review and the title of the magazine interested him very much. He asked me what the magazine was about, and I told him. He then asked me if I was really interested in ghosts and their stories. I told him that I was.

"In our village we have a gentleman who has a family ghost" said my companion.

"What kind of thing is a family ghost?" I asked.

"Oh—the ghost comes and has his dinner with my neighbour every night," said my companion. "Really—must be a very funny ghost" I said. "It is a fact—if you stay for a day in my village you will learn everything."

I at once decided to break my journey in the village. It was about 2 in the afternoon when I got down at the Railway Station—procured a hackney carriage and, ascertaining the name and address of the gentleman who had the family ghost, separated from my old companion.

[Pg 40] I reached the house in 20 minutes, and told the gentleman that I was a stranger in those parts and as such craved leave to pass the rest of the day and the night under his roof. I was a very unwelcome guest, but he could not kick me out, as the moral code would not permit it. He, however, shrewdly guessed why I was anxious to pass the night at his house.

Of course, my host was very kind to me. He was a tolerably rich man with a large family. Most of his sons were grown-up young men who were at College in Calcutta. The younger children were of course at home.

At night when we sat down to dinner I gently broached the subject by hinting at the rumour I had heard that his house was haunted. I further explained to him that I had only come to ascertain if what I had heard was true. He told me (of course it was very kind of him) that the story about the dinner was false, and what really happened was this:—

"I had a younger brother who died 2 years ago. He was of a religious turn of mind and passed his time in reading religious books and writing articles about religion in papers. He died suddenly one night. In fact he was found dead in [Pg 41] his bed in the morning. The doctors said it was due to failure of heart. Since his death he has come and slept in the room, which was his when he was alive and is his still. All that he takes is a glass of water fetched from the sacred river Ganges. We put the glass of water in the room and make the bed every evening; the next morning the glass is found empty and the bed appears to have been slept upon."

"But why did you begin?—" I asked.

"Oh—One night he appeared to me in a dream and asked me to keep the water and a clean bed in the room—this was about a month after his death," said my host.

"Has anybody ever passed a night in the room to see what really happens?" I asked.

"His young wife—or rather widow passed a night in that room—the next morning we found her on the bed—sleeping—dead—from failure of heart—so the doctors said."

"Most wonderful and interesting." I remarked.

"Nobody has gone to that part of the house since the death of the poor young widow" said my host. "I have got all the doors of the room [Pg 42] securely screwed up except one, and that too is kept carefully locked, and the key is always with me."

After dinner my host took me to the haunted room. All arrangements for the night were being made; and the bed was neat and clean.

A glass of the Ganges water was kept in a corner with a cover on it. I looked at the doors, they were all perfectly secure. The only door that could open was then closed and locked.

My host smiled at me sadly "we won't do all this uselessly" he said "this is a very costly trick if you think it a trick at all, because I have to pay to the servants double the amount that others pay in this village—otherwise they would run away. You can sleep at the door and see that nobody gets in at night."

I said "I believe you most implicitly and need not take the precaution suggested." I was then shown into my room and everybody withdrew.

My room was 4 or 5 apartments off and of course these apartments were to be unoccupied.

As soon as my host and the servants had withdrawn, I took up my candle and went to the locked door of the ghostly room. With the lighted [Pg 43] candle I covered the back of the lock with a thin coating of soot or lamp-black. Then I scraped off a little dried-up whitewash from the wall and sprinkled the powder over the lamp-black.

"If any body disturbs the lock at night I shall know it in the morning" I thought. Well, the reader could guess that I had not a good sleep that night. I got up at about 4-30 in the morning and went to the locked door. My seal was intact, that is, the lamp-black with the powdered lime was there just as I had left it.

I took out my handkerchief and wiped the lock clean. The whole operation took me about 5 minutes. Then I waited.

At about 5 my host came and a servant with him. The locked door was opened in my presence. The glass of water was dry and there was not a drop of water in it. The bed had been slept upon. There was a distinct mark on the pillow where the head should have been—and the sheet too looked as if somebody had been in bed the whole night.

I left the same day by the after-noon train having passed about 23 hours with the family in the haunted house.

This story need not have been written. It is too sad and too mysterious, but since reference has been made to it in this book, it is only right that readers should know this sad account.

Uncle was a very strong and powerful man and used to boast a good deal of his strength. He was employed in a Government Office in Calcutta. He used to come to his village home during the holidays. He was a widower with one or two children, who stayed with his brother's family in the village.

Uncle has had no bed-room of his own since his wife's death. Whenever he paid us a visit one of us used to place his bed-room at uncle's disposal. It is a custom in Bengal to sleep with one's wife and children in the same bed-room. So whenever Uncle turned up I used to give my bed-room to him as I was the only person without children. On such occasions I slept in one of the "Baithaks" (drawing-rooms). A Baithak is a drawing-room and guest-room combined.

In rich Bengal families of the orthodox style the "Baithak" or "Baithak khana" is a very large [Pg 45] room generally devoid of all furniture, having a thick rich carpet on the floor with a clean sheet upon it and big takias (pillows) all around the wall. The elderly people would sit on the ground and lean against the takias; while we, the younger lot, sat upon the takias and leaned against the wall which in the case of the particular room in our house was covered with some kind of yellow paint which did not come off on the clothes.

Sometimes a takia would burst and the cotton stuffing inside would come out; and then the old servant (his status is that of an English butler, his duty to prepare the hookah for the master) would give us a chase with a lathi (stick) and the offender would run away, and not return until all incriminating evidence had been removed and the old servant's wrath had subsided.

Well, when Uncle used to come I slept in the "Baithak" and my wife slept somewhere in the zenana, I never inquired where.

On this particular occasion Uncle missed the train by which he usually came. It was the month of October and he should have arrived at 8 p.m. My bed had been made in the Baithak. But the 8 p.m. train came and stopped and passed on and Uncle did not turn up.

[Pg 46] So we thought he had been detained for the night. It was the Durgapooja season and some presents for the children at home had to be purchased and, we thought, that was what was detaining him. And so at about 10 p.m. we all retired to bed. The bed that had been made for me in the "Baithak" remained there for Uncle in case he turned up by the 11 p.m. train. As a matter of fact we did not expect him till the next morning.

But as misfortune would have it Uncle did arrive by the 11 o'clock train.

All the house-hold had retired, and though the old servant suggested that I should be waked up, Uncle would not hear of it. He would sleep in the bed originally made for me, he said.

The bed was in the central Baithak or hall. My Uncle was very fond of sleeping in side-rooms. I do not know why. Anyhow he ordered the servant to remove his bed to one of the side-rooms. Accordingly the bed was taken to one of them. One side of that room had two windows opening on the garden. The garden was more a park-like place, rather neglected, but still well wooded abounding in jack fruit trees. It used to be quite shady and dark during the day there. On [Pg 47] this particular night it must have been very dark. I do not remember now whether there was a moon or not.

Well, Uncle went to sleep and so did the servants. It was about 8 o'clock the next morning, when we thought that Uncle had slept long enough, that we went to wake him up.

The door connecting the side-room with the main Baithak was closed, but not bolted from inside; so we pushed the door open and went in.

Uncle lay in bed panting. He stared at us with eyes that saw but did not perceive. We at once knew that something was wrong. On touching his body we found that he had high fever. We opened the windows, and it was then that Uncle spoke "Don't open or it would come in—"

"What would come in Uncle—what?" we asked.

But uncle had fainted.

The doctor was called in. He arrived at about ten in the morning. He said it was high fever—due to what he could not say. All the same he prescribed a medicine.

[Pg 48] The medicine had the effect of reducing the temperature, and at about 6 in the evening consciousness returned. Still he was in a very weak condition. Some medicine was given to induce sleep and he passed the night well. We nursed him by turns at night. The next morning we had all the satisfaction of seeing him all right. He walked from the bed-room, though still very weak and came to the Central Baithak where he had tea with us. It was then that we asked what he had seen and what he had meant by "It would come in."

Oh how we wish, we had never asked him the question, at least then.

This was what he said:—

"After I had gone to bed I found that there were a few mosquitoes and so I could not sleep well. It was about midnight when they gradually disappeared and then I began to fall asleep. But just as I was dozing off I heard somebody strike the bars of the windows thrice. It was like three distinct strokes with a cane on the gratings outside. 'Who is there?' I asked; but no reply. The striking stopped. Again I closed my eyes and again the same strokes were repeated. This time I nearly lost my temper; I thought it was some [Pg 49] urchin of the neighbourhood in a mischievous mood. 'Who is there?' I again shouted—again no reply. The striking however stopped. But after a time it commenced afresh. This time I lost my temper completely and opened the window, determined to thrash anybody whom I found there—forgetting that the windows were barred and fully 6 feet above the ground. Well in the darkness I saw, I saw—."

Here uncle had a fit of shivering and panting, and within a minute he lost all consciousness. The fever was again high. The doctor was summoned but this time his medicines did no good. Uncle never regained consciousness. In fact after 24 hours he died of heart failure the next morning, leaving his story unfinished and without in any way giving us an idea of what that terrible thing was which he had seen beyond the window. The whole thing remains a deep mystery and unfortunately the mystery will never be solved.

Nobody has ventured to pass a night in the side-room since then. If I had not been a married man with a very young wife I might have tried.

One thing however remains and it is this that though uncle got all the fright in the world in [Pg 50] that room, he neither came out of that room nor called for help.

One cry for help and the whole house-hold would have been awake. In fact there was a servant within 30 yards of the window which uncle had opened; and this man says he heard uncle open the window and close and bolt it again, though he had not heard uncle's shouts of "Who is there?"

Only this morning I read this funny advertisement in the Morning Post.

"Haunted Houses.—Man and wife, cultured and travelled, gentle people—having lost fortune ready to act as care-takers and to investigate in view of removing trouble—."

Well—in a haunted house these gentle people expect to see something. Let us hope they will not see what our Uncle saw or what the Major saw.

This advertisement clearly shows that even in countries like England haunted houses do exist, or at least houses exist which are believed to be haunted.

If what we see really depends on what we think or what we believe, no wonder that there are [Pg 51] so many more haunted houses in India than in England. This reminds me of a very old incident of my early school days. A boy was really caught by a Ghost and then there was trouble. We shall not forget the thrashing we received from our teacher in the school; and the fellow who was actually caught by the Ghost—if Ghost it was, will never say in future that Ghosts don't exist.

In this connection it may not be out of place to narrate another incident, though it does not fall within the same category with the main story that heads this chapter. The only reason why I do so is that the facts tally in one respect, though in one respect only, and that is that the person who knew would tell nothing.

This was a friend of mine who was a widower. We were in the same office together and he occupied a chair and a table next but one to mine. This gentleman was in our office for only six months after narrating the story. If he had stayed longer we might have got out his secret, but unfortunately he went away; he has gone so far from us that probably we shall not meet again for the next 10 years.

It was in connection with the "Smith's dead wife's photograph" controversy that one day one [Pg 52] of my fellow clerks told me that a visit from a dead wife was nothing very wonderful, as our friend Haralal could testify.

I always took of a lot of interest in ghosts and their stories. So I was generally at Haralal's desk cross-examining him about this affair; at first the gentleman was very uncommunicative but when he saw I would give him no rest he made a statement which I have every reason to believe is true. This is more or less what he says.

"It was about ten years ago that I joined this office. I have been a widower ever since I left college—in fact I married the daughter of a neighbour when I was at college and she died about 3 years afterwards, when I was just thinking of beginning life in right earnest. She has been dead these 10 years and I shall never marry again, (a young widower in good circumstances, in Bengal, is as rare as a blue rose).

"I have a suite of bachelor rooms in Calcutta, but I go to my suburban home on every Saturday afternoon and stay there till Monday morning, that is, I pass my Saturday night and the whole of Sunday in my village home every week.

"On this particular occasion nearly eight years ago, that is, about a year and a half after the [Pg 53] death of my young wife I went home by an evening train. There is any number of trains in the evening and there is no certainty by which train I go, so if I am late, generally everybody goes to bed with the exception of my mother.

"On this particular night I reached home rather late. It was the month of September and there had been a heavy shower in the town and all tram-car services had been suspended.

"When I reached the Railway Station I found that the trains were not running to time either. I was given to understand that a tree had been blown down against the telegraph wire, and so the signals were not going through; and as it was rather dark the trains were only running on the report of a motor trolly that the line was clear. Thus I reached home at about eleven instead of eight in the evening.

"I found my father also sitting up for me though he had had his dinner. He wanted to learn the particulars of the storm at Calcutta.

"Within ten minutes of my arrival he went to bed and within an hour I finished my dinner and retired for the night.

" [Pg 54] It was rather stuffy and the bed was damp as I was perspiring freely; and consequently I was not feeling inclined to sleep.

"A little after midnight I felt that there was somebody else in the room.

"I looked at the closed door—yes there was no mistake about it, it was my wife, my wife who had been dead these eighteen months.

"At first I was—well you can guess my feeling—then she spoke:

"'There is a cool bed-mat under the bedstead; it is rather dusty, but it will make you comfortable.

"I got up and looked under the bedstead—yes the cool bed-mat was there right enough and it was dusty too. I took it outside and I cleaned it by giving it a few jerks. Yes, I had to pass through the door at which she was standing within six inches of her,—don't put any questions; Let me tell you as much as I like; you will get nothing out of me if you interrupt—yes, I passed a comfortable night. She was in that room for a long time, telling me lots of things. The next morning my mother enquired with whom I was talking and I told her a lie. I said I was reading [Pg 55] my novel aloud. They all know it at home now. She comes and passes two nights with me in the week when I am at home. She does not come to Calcutta. She talks about various matters and she is happy—don't ask me how I know that. I shall not tell you whether I have touched her body because that will give rise to further questions.

"Everybody at home has seen her, and they all know what I have told you, but nobody has spoken to her. They all respect and love her—nobody is afraid. In fact she never comes except on Saturday and Sunday evenings and that when I am at home."

No amount of cross-examination, coaxing or inducement made my friend Haralal say anything further.

This story in itself would not probably have been believed; but after the incident of "His dead wife's picture" nobody disbelieved it, and there is no reason why anybody should. Haralal is not a man who would tell yarns, and then I have made enquiries at Haralal's village where several persons know this much; that his dead wife pays him a visit twice every week.

[Pg 56] Now that Haralal is 500 miles from his village home I do not know how things stand; but I am told that this story reached the ears of the Bara Saheb and he asked Haralal if he would object to a transfer and Haralal told him that he would not.

I shall leave the reader to draw his own conclusions.

Nothing is more common in India than seeing a ghost. Every one of us has seen ghost at some period of his existence; and if we have not actually seen one, some other person has, and has given us such a vivid description that we cannot but believe to be true what we hear.

This is, however, my own experience. I am told others have observed the phenomenon before.

When we were boys at school we used, among other things, to discuss ghosts. Most of my fellow students asserted that they did not believe in ghosts, but I was one of those who not only believed in their existence but also in their power to do harm to human beings if they liked. Of course, I was in the minority. As a matter of fact I knew that all those who said that they did not believe in ghosts told a lie. They believed in ghosts as much as I did, only they had not the courage to admit their weakness and differ boldly from the sceptics. Among the lot of unbelievers was one Ram Lal, a student of the Fifth Standard, who swore that he did not believe in ghosts and [Pg 58] further that he would do anything to convince us that they did not exist.

It was, therefore, at my suggestion that he decided to go one moon-light night and hammer down a wooden peg into the soft sandy soil of the Hindoo Burning Ghat, it being well known that the ghosts generally put in a visible appearance at a burning ghat on a moon-light night. (A burning ghat is the place where dead bodies of Hindoos are cremated).

It was the warm month of April and the river had shrunk into the size of a nullah or drain. The real pukka ghat (the bathing place, built of bricks and lime) was about 200 yards from the water of the main stream, with a stretch of sand between.

The ghats are only used in the morning when people come to bathe, and in the evening they are all deserted. After a game of football on the school grounds we sometimes used to come and sit on the pukka ghat for an hour and return home after nightfall.

Now, it was the 23rd of April and a bright moon-light night, every one of us (there were about a dozen) had told the people at home that there was a function at the school and he might [Pg 59] be late. On this night, it was arranged that the ghost test should take place.